Reflection as Renewal: Why Education Needs to Slow Down to Move Forward

By Christer Windeløv-Lidzélius

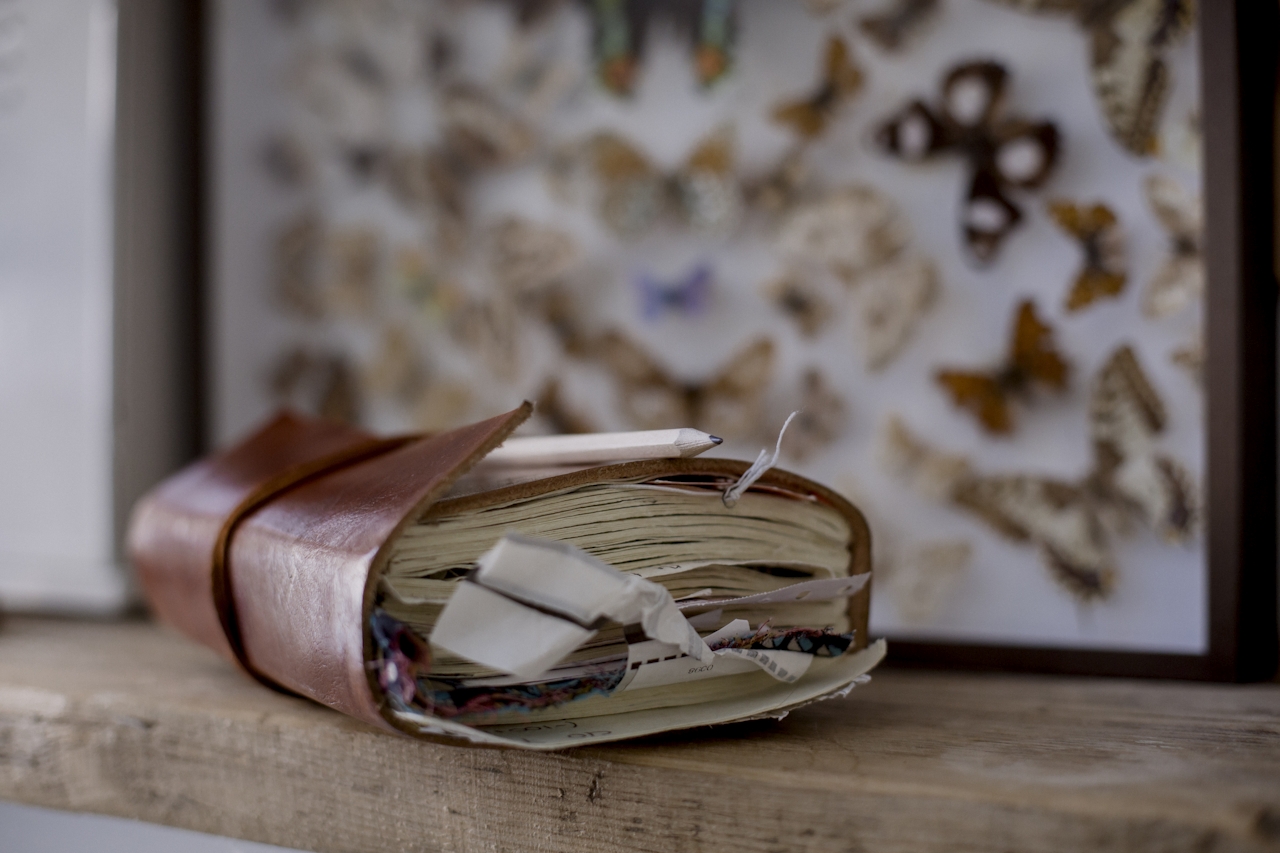

Between doing and knowing lies a quiet space—the moment when experience turns into understanding. That space is where reflective practice begins. Not as a formal process, but as a way of being—a posture of curiosity, care, and responsibility. In education, it is nothing less than the architecture of attentiveness.

Reflective practice is often spoken of in relation to teaching, but it is far more than a method for educators. It is a foundational ethic—a way of thinking and designing that threads through curriculum, pedagogy, school culture, and ultimately, student growth. It is what turns routines into rituals, data into dialogue, and experience into understanding. In a world that moves ever faster, reflection is what allows learning to breathe.

The Reflective Teacher and the Living Curriculum

At the heart of reflective practice is the teacher—not as a technician delivering prefabricated knowledge, but as an artisan of learning. Donald Schön’s (1983) now-classic distinction between reflection-in-action and reflection-on-action illuminates the artistry of teaching as improvisation and inquiry. The first happens in the moment—thinking while teaching, adjusting in real time—while the second occurs afterward, when one steps back to analyze what worked, what didn’t, and why. Later scholars have added reflection-for-action, emphasizing foresight and intention: how we prepare differently next time because we have learned to see differently now.

More recent frameworks, such as Jay and Johnson’s (2002) three-dimensional model of descriptive, comparative, and critical reflection and Farrell’s (2018) five-level model extending from philosophy to practice, illustrate how reflection has evolved into a structured, ongoing inquiry rather than a discrete moment of thought.

A reflective practitioner does not treat the curriculum as static, but as a living organism—responsive to the students in the room, the questions that arise, and the crises in the world outside. They ask: Is this still relevant? Whose voices are missing? What new connections might bring this unit alive?

When curriculum is approached reflectively, it becomes more than a syllabus—it becomes a co-authored map between teacher and student. As Dewey (1933) insisted, reflection is what makes experience educative rather than merely habitual.

Sometimes this reflection begins in the smallest moment—a hesitation before answering a question, a pause to really listen. Such moments, multiplied over time, quietly transform a teacher’s practice.

Classroom as Reflective Space

The classroom, then, becomes the crucible of reflection—not just for teachers, but for students. A reflective classroom is one where learners are not passive recipients but active co-constructors of knowledge. It is a space where they are invited to notice their own thinking, to consider multiple perspectives, to make connections, and to return to their assumptions with new eyes.

This kind of classroom is not born of charisma or ideology alone—it is designed. And that design is underwritten by educators who are in constant conversation with their practice: journaling, dialoguing, adjusting, and sometimes starting over.

In a 2022 study, Kılıç found that pre-service teachers—that is, university students in teacher-training programs before entering the profession—who engaged in structured reflection improved not only in classroom management and planning but in their ability to adapt in real time. The result was more engaging, student-centered learning environments (Kılıç, 2022).

Reflection and Student Outcomes

Too often, reflective practice is seen primarily as a tool for teacher development. But this view is too narrow. When reflection is embedded into the fabric of education, it has ripple effects far beyond pedagogy.

Recent studies show that reflective teaching is correlated with stronger student engagement, improved classroom climate, and greater learner autonomy (Apilado, 2024). At a university of technology in South Africa, a program integrating structured reflection techniques into instruction led to measurable reductions in first-year dropout rates (Maphosa & Wadesango, 2014). Students weren’t just staying—they were learning better.

Other research highlights how reflective goal-setting and metacognitive strategies improve student well-being, fostering academic resilience and a stronger sense of purpose (van Zyl, 2023). A reflective school environment promotes not only cognition but care. It creates space for belonging, and in doing so, addresses some of the most pressing mental-health and equity challenges in today’s classrooms.

A Culture of Reflection

Reflection is not just an individual capacity—it is a cultural condition. Schools that embrace reflective practice institutionally create space for collaboration, iteration, and trust. They build time into the schedule not only for planning, but for thinking. They view feedback as dialogue rather than judgment. They treat missteps as data, not failure.

Kosloski and Reed’s (2010) work on professional-development ROI highlights how sustained reflective inquiry among educators leads to measurable improvements in instructional quality and student performance. The gains are not simply academic—they are systemic. Where reflection flourishes, coherence and alignment follow.

I have seen entire faculties change tone when reflection becomes shared habit rather than solitary labor—meetings shift from compliance to curiosity, and language grows lighter, more hopeful.

From Classrooms to Systems

On a wider scale, reflective practice is the missing infrastructure in many education systems. It is the mechanism through which programs are revised, policies are humanized, and budgets are realigned with what actually works. The Tennessee Department of Education (2020) explored this through its Academic ROI model, demonstrating how strategic, reflective decision-making can elevate both efficiency and equity.

But for this to happen, systems must be willing to learn—not just through metrics, but through meaning. They must be willing to listen: to teachers, to students, to communities. Reflection, in this sense, is not only a process but a politics. It is a declaration that learning is not linear, and progress is not always a straight line.

As artificial intelligence, data analytics, and performance pressures reshape classrooms, reflection reminds us that education’s deepest value lies not in acceleration but in awareness.

In Closing: Reflection as Renewal

To reflect is to return—but not to retreat. It is to look again, and this time, to see with more understanding. In a time when education is under pressure to innovate, to perform, to digitize—reflection offers something deeper: the capacity to renew.

Perhaps that is the quiet gift of reflection: the space between doing and knowing, where education remembers what it was meant to be. A reflective education is not just more effective. It is more human.

References

Apilado, J. C. (2024). Teachers’ Reflective Practices and Students’ Academic Engagement in Junior High Schools in Davao City. International Journal of Innovative Science and Research Technology, 9(4), 225–232.

Dewey, J. (1933). How we think: A restatement of the relation of reflective thinking to the educative process. D.C. Heath and Company.

Farrell, T. S. C. (2018). Reflective practice in language education: Beyond the concept of reflection. Routledge.

Jay, J. K., & Johnson, K. L. (2002). Capturing complexity: A typology of reflective practice for teacher education. Teaching and Teacher Education, 18(1), 73–85

Kılıç, Z. (2022). Reflections of pre-service science teachers’ reflection-in, on, and for-action processes on their teaching practices. International Journal of Education in Mathematics, Science and Technology, 10(1), 49–69.

Kosloski, T., & Reed, P. (2010). Determining return on investment for professional development in public education: A model. Journal of Case Studies in Education, 2, 1–15.

Maphosa, C., & Wadesango, N. (2014). Using reflective practices to reduce dropout rates among first-year students: A South African perspective. Journal of Social Sciences, 40(2), 133–142.

Schön, D. A. (1983). The reflective practitioner: How professionals think in action. Basic Books. Tennessee Department of Education. (2020). Academic return on investment: A guide to strategic budgeting in education.

van Zyl, L. (2023). Reflective goal setting and first-year student well-being: A randomized control study. Journal of College Student Development, 64(1), 21–38.

About Christer Windeløv-Lidzélius

Academic Advisor – Professor & Strategy / Design Leader

As a principal of a private university for 17 years, Christer has seen both the immense value of deep reflective practice and how challenging it is to weave it into curricula. He joined Rflect because it provides a unique opportunity to solve that challenge and scale reflective practice to unlock human flourishing.

LinkedIn

Website